GLOW Season 1 Erratum: Not a Camcorder

Whenever a series is set in a particular era, there’s a certain allowance for errors: cars that didn’t appear until a year later, historical figures that weren’t yet in power, music that wasn’t broadcast until 2 years later. You know: minor, semi-deliberate slips that work better for a show’s dramatic punch and give the perception of accuracy… but sometimes a boo-boo is a bit glaring.

There’s a scene in Joe Dante’s Matinee (1993), set during the 1960s Cuban Missile Crisis, in which a radio is visible in a kid’s bedroom. I’m not an expert in RCA radios, but I remember shaking my head with disapproval because I had that radio in the early seventies, because my mother used to babysit the monster child of an RCA employee who would gift us with RCA LP’s – classical, opera, jazz, Dr. Seuss – plus that specific radio. It didn’t ruin the film, but in spite of the best efforts by ace set decorators and prop masters, the irritation of a continuity boo-boo lingers.

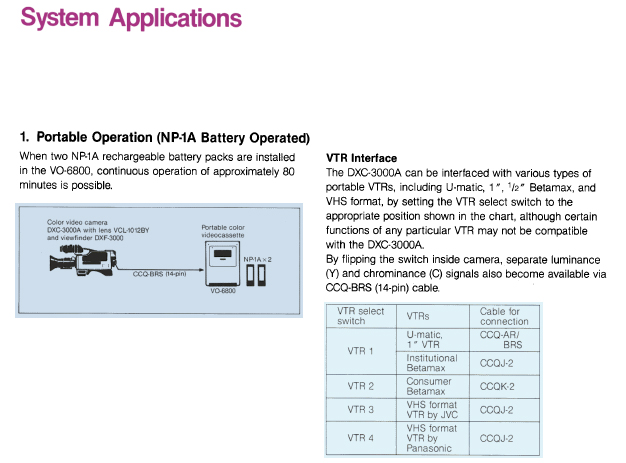

The error in GLOW: Season 1 is understandable because someone probably figured the Sony camera featured in Episode 6 (“This Is One of Those Moments”) was big and bulky and looked period enough that it could pass for a camcorder, but the problem is it’s not a camcorder. Without getting technical, here’s a short chronicle of the models leading up to the Sony DXC-3000 camera used in Ep. 6.

Early news (ENG) cameras involved a lens and camera head (main body), eyepiece, mic, battery and / or AC adapter, and a fat cable that connected the camera proper to either a VCR or a Camera Control Unit (CCU).

The CCU was used in studio environments and allowed a user to remotely do white balancing, focusing, aperture setting, and more , leaving the camera operator to shoot and take directorial cues through an intercom or headset.

Inside of a studio and in the field, the camera mandated a separate VCR because early ENG cameras did not feature a dockable mount for recorders – you had a side pack that someone carried or you carried that powered and recorded picture & sound from the camera.

Early recording formats included ¾” U-Matic, a chunky, indestructible tape format that even in its compact form mandated a deadly-heavy recorder; it was superseded by U-Matic SP, Betacam, and in prosumer and cable TV realms S-VHS and Hi8. You could even use VHS & VHS-C.

Sony’s DXC-1640 is a good example of an early intro ENG camera that was compact in its day, and followed the usual connection system of camera +cable + VCR. This model used Sony’s own Trinicon colour tube.

That model was soon followed by the DXC-1800, which was bigger, featured a shoulder mount, and used a Saticon tube.

Sony replaced it with the Trinicon DXC-1820, which I remember we used in film school briefly, along with a compact U-Matic recorder.

Around the mid- to late 1980s Sony offered both 3-tube and 3-CCD cameras, and the DXC-M2 and later M3 were eventually eclipsed by the DXC-3000, which is the model seen in Ep. 6.

In its day, the 3000 was reportedly a solid camera, and like the aforementioned M-series, had a sensor for each colour: red, green, and blue, and this model supposedly had the biggest CCD chips Sony ever shoved into an ENG camera.

It is a big camera, but it’s NOT a camcorder. It follows the same older design in which the camera needs a separate VCR deck to capture picture & sound. There is a slot for a battery and larger battery pack, but no VCR, and the camera cannot function without battery or cable.

Period.

Which is why its use in GLOW is fairly time-wise correct (my camera’s manual is stamped 1987), but its use is 100% incorrect, because there should be a cable & recorder hanging from the guy’s shoulder, or at least resting to the side of the ring. Here’s frame grabs of the incorrect depiction:

Now, I would post video footage of what the camera can produce, but my baby’s in storage and the original test footage has disppeared, so I’ll close with another brochure snapshot that features some of the components you could buy, in terms of optional lenses, cable lengths, CCUs, portable & studio VCRs, and Special Effects Units (SEG) that allowed for mixing and fancy-schmancy wipes.

Among the pictured gear is the SEG-2550A, a very nice mixer that offered some programmable steps for the wipes and mixes. It’s more compact than expected, but quite heavy, packed with multiple circuit boards and a needed fan to keep the guts cool. This model often appears for sale, perhaps illustrating how widely used Sony’s gear was in field and studio ENG environments.

In university, we initially used the -U-Matic SP recorder-player, which perhaps explains my attraction to chunky tactile gear, but that devotion doesn’t extend to the tape media for a really simple reason: even though U-Matic machines show up for sale online, in terms of longevity & functionality, they need to be kept running to be happy, they weigh a tonne, and when they break down you have a tough journey getting such vintage gear repaired. As much as I would love to still own one of those monsters, they’re tough to maintain in working order, and parts would probably be a nightmare to find (if not costly, should Sony still have some in far-off warehouses).

The lack of moving parts (knobs and sliders excepted) in SEG’s may be an important reason they can be bought used with relative confidence, and more often issues arise from bad caps and power supplies on mixers 35-40 years in age. The 2550A is way ahead of the Sony SEG-1 which had just one circuit board.

The only mixers that I’ve bought and require major restoration are the SEG-1, and Shintron’s 370 Chromatic Series (see crochambeau’s machine log for additional stills + a short bit at Kino Digital Video); seems those units have caps that just don’t last, but they do date from the late 1970s….

Mark R. Hasan, Editor

Big Head Amusement