PRIVATE PAGE — Review: Sony VX3 Hi8 Camcorder, Part 1 – Consumer to Prosumer

Sony VX3 Hi8 Camcorder

Part 1: Consumer to Prosumer

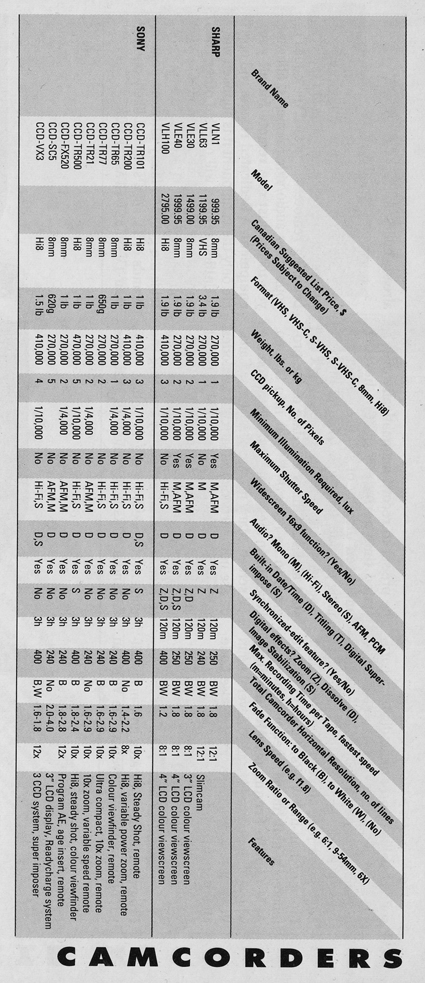

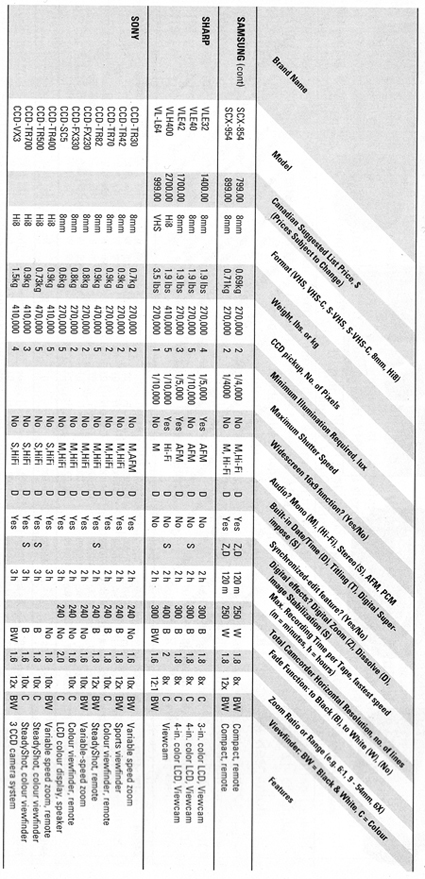

When I started a video transfer business around 1991-1992, my first camcorder was the Sony Hi8 CCD-V801, which offered good quality image, in-camera editing features, and ease & portability, but I remember my eyes widened when a year later I read of Sony’s upcoming CCD-VX3 (or VX1, as it was known in Japan and in Europe), a Hi8 camcorder that marked the company’s upper tier model for the burgeoning prosumer market.

The chief addition that distinguished the VX3 from Sony’s cheaper consumer grade models was having 3 CCD (charge coupled device) chips instead of 1, and of course, the price – roughly $3500 USD / $4000 CAD, which in today’s currency amounts to $7350 USD / $9200 CAD.

So… What is the difference between prosumer and consumer products?

I’ll revisit each of the tiers in Part 2, 3CCDs, Baby! in greater detail, but Prosumer evolved into what can be described as a middle ground between consumer, industrial, and professional broadcast quality products. Taking camcorders as an example, most consumer models would offer basic record & playback features (and insert audio & video edits in mid-price models), have composite RCA video and audio output, a fairly cheap fixed lens with very modest or severely limited zoom, wide, and macro features; mono or stereo recording & playback; and a single CCD image sensor which had limited sensitivity for low light situations. There might be manual controls for aperture, white balance, and gain, or manual control for very dark & very bright environments.

Using a home-based VCR as an example, a high end consumer model would likely have Hi-Fi stereo audio, insert video and audio editing features using a flying erase head for seamless edits, and if it was a S-VHS deck, output video as composite via RCA connector, and S-VHS’s separate luminance and chrominance (aka Y/C) signal through a 4-pin DIN plug.

Alternatively, a prosumer deck would have a basic time base corrector (aka TBC) to ensure stable video signals being output (less noise, more natural and stable colour reproduction), the same Y/C connector if it’s a S-VHS deck, and perhaps BNC bayonet plugs for composite video instead of easy-to-slide-off RCA connectors (which also tended to lack the more firm mounting on circuit boards compared to BNCs).

With professional decks, edits using a matching controller would be 100% accurate and would use the video signal’s control track or industry-standard SMTPE time code, whereas prosumer decks and their respective controller would have an accuracy rate of +/- 4 frames – meaning they’d be close to exact, but not on the mark, and allow for slippage.

Not unlike crash editing with an audio cassette deck, edits using standard consumer VCRs lacking any editing controller connectivity would depend on one’s instincts, and luck in timing the readied playback VCR or camera with the recording deck to get a reasonably okay, a sort of rough, but a generally tolerable edit.

And unlike professional and prosumer decks, not all consumer VCRs would have flying erase heads that enabled smooth transitions between shots, and prevent sudden image jitter and dropouts in both video and audio tracks.

Bottom line: the more you went up the consumer and prosumer model chain (and higher price point), the more features would allow one to be both technically proficient, and more creative.

The V801, the VX3, and the V5000:

Differences and Retentia

For a price comparison between Sony Hi8 models from specific tiers circa 1992, my V801 cost around $1800 CAD. The model up, a V5000, also a single CCD camera, cost roughly $3500 CAD, and although loaded with a variety of features, there were a few quirks.

The V5000 had a variety of digital effects – strobing, solarizing, multiple images – but a major feature which it lacked was fully manual aperture control; only extreme brightness or darkness could be adjusted manually on the V5000. The VX3 and V801 also used Sony’s proprietary RC time code which could be used for editing, although for reasons I’ll get into shortly, 8mm videotape was among the worst formats to use for editing.

Unlike the VX3 and V801 which lack a TBC, the V5000’s TBC kicks in automatically (and only) during playback to ensure stable, clean video signals during dubbing and editing. The VX3, though, has an additional feature called Chroma Noise Reduction (CNR) which “minimizes color noise or irregular colors when playing back a tape,” although as the manual states, it could also backfire and create a “color lag” if the video quality is unstable or messy. All three camera models (V801, VX3, and V5000) have the lesser “edit” feature that’s also found on Sony’s Betamax decks that offers a kind of image stabilization (or as the V5000 manual states, “to minimize the sound and picture deteriorations” when editing and dubbing).

The V5000 could record digital PCM (Pulse Code Modulation) stereo audio with recording levels that could be controlled manually; both the VX3 and the V801 recorded only analogue AFM stereo with no level control. PCM audio, though, wasn’t new to the consumer tier, as Sony introduced digital audio via its PCM-F1 encoder-decoder in 1978, which recorded digital audio onto Betamax tapes using a portable deck. Subsequent Betamax home decks (and those by other brands who made Beta and VHS decks) in the 1980s had the capability to record and play PCM audio when connected to a decoder (by any brand).

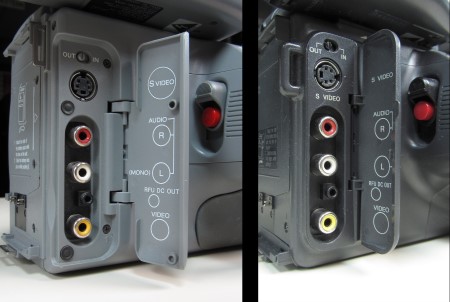

Although the V5000 recorded PCM audio, it only output analogue audio via stereo RCA connectors. However, unlike lower tier camcorders, the VX3 and V801 had a panel of switchable input-outputs, which enabled them to be used as players and recorders. In addition to stereo RCA connectors, the three models have composite RCA and 4-pin DIN Y/C connectors for video.

The V5000 has one extra feature that makes it unique above the other two: separate audio and video inputs and outputs, which allows the camcorder to be used as a pass-through. This feature is more important with minidv camcorders with firewire, as these camcorders can be used to send audio and video from another source (like a VHS deck) via firewire to a computer for digital capture. So why does this matter with the V5000? I mention this only as a teaser, because both the V801 and V5000 are notorious for having bad capacitors which ultimately cause the camcorders to rot and die, and become doorstops.

My V5000 can no longer film any sound or images, but it can still pass through a video signal, and as the capacitors are rotting at a slower pace, the camcorder organically glitches and corrupts video, and in a separate series of posts, I’ll demonstrate how dying and rotting VCRs and camcorders may still have a bit of use for creating glitch videos before they become paperweights (or boat anchors) like their old batteries.

A Period of Transitions

1990-1992 can be regarded as a weird transition period for Sony, because while you had consumer Video8 and Hi8 camcorders in black casing – the black-clad V5000 was clearly the upper tier in the line – the V801’s dark grey casing and lack of digital effects on the prior line make one suspect it was an early prosumer design that was developed by a different department team – hence its lack of PCM audio and gimmicky effects in the V5000. I’m just postulating, but during its development, the VX3 was perhaps too close to completion to kill, and too far ahead with its 3 CCD architecture to radically modify and fit additional new features, such as PCM meters.

In spite of a lighter gray case, the VX3 still looks like the V801’s big brother, although it uses a tape loading mechanism similar to the Hi8 TRV line where the whole tape carriage lifts and pops open instead of a vertical side-loading, pop-up tray shared with the V801 and V5000.

The side buttons for auto and manual settings and slim LCD screen are almost identical between both models.

I loved using my V801 – it was small, very light & portable, had editing features that made it perfect for punching in titles from an ancient 1982 Quantafont character generator so I could create a dubbing master without going an extra generation, and it was decent for low light tapings, but its lens was very basic, and the plastic housing quite cheap. The heads also wore out 3 years into use, and cost almost $400 to replace.

From a design standpoint, those side buttons for manually setting aperture, gain, and shutter differed in side and shape, so after a few uses, you could ‘feel’ your way along the control to find the right one for aperture, shutter speed, gain, and white balance – a really helpful feature when I was taping dance performances in a darkened auditorium.

For contrast, Sony’s professional grade Hi8 camera, the 3-CCD EVW-300, cost around $10,000 CAD, and used high quality detachable lenses used for broadcast productions, and had a resolution of around 700 lines – near HD quality. Although the VX3 is rated as being standard definition 4:3 480i, the robustness of its colour and detail arguably make it one of the best pre-minidv / Digital8 camcorders whose image, when piped directly from the camera to a digital capture device, suffers less severe artifacting compared to a Hi8 tape recording.

So herein lies another conundrum: while a camera’s imaging centre, better known as the camera head, might have a high resolution of 700 lines, the recorded resolution is wholly dependent on the tape format; so while the EVW-300 might output 700i, once recorded to tape, the sharp image is knocked down to Hi8’s roughly 400i line ceiling.

That seems like a contradiction, in terms of a camera being designed with higher resolution than a tape-based format, but camcorders are ostensibly descendants of studio cameras, and within a broadcast studio environment, you want the camera head to capture the best possible image so that as it travels down the line of cables, routers, camera control units, switchers, mixers, and hit the airwaves live, the qualitative end result survives its final destination – one’s own TV set.

Using the music medium in a simplified example: audio is recorded at a high bit rate, then mixed down and mastered so it still sounds good on its custom LP, cassette, CD, and the various digital formats. Put another way: if an album was superbly crafted, your 320 kbps MP3 won’t sound like flattened aural crap.

Like an album’s 24bit digital multitrack master mix, the camera’s high optical resolution ensures the best possible image is recorded to tape, and can survive as it’s edited and recorded anew to tape again, and again. The upside for vintage video connoisseurs – especially analogue – is that you have 2 choices with camcorders capable of outputting composite, Y/C, and component video: you can get a lo-fi look by recording to tape, or send the sharper raw video from the camera to external sources, such as a digitally capture, uncompressed MOV or AVI file, and have more flexibility in fiddling with the video before it’s edited and rendered into a less space-hogging format like MP4.

The VX3 wasn’t rare is 1992 – it was just expensive – and Sony’s decision to discontinue the model in 1995 coincided with the introduction of smaller-sized minidv format, of which the first consumer cameras began to appear that same year. If we accept an assumption that Sony’s engineers were constantly trying to find ways to push existing formats to their maximum potential and lifespan within the consumer market, and from their incessant noodling, create new tape formats, then it makes sense to assume the VX3 had the perfect architecture for the VX1000, which ostensibly made the VX3 redundant less that 3 years after its release, and the V801 obsolete when cheaper consumer models had funky, trippy digital effects and transitions between starting & stopping a recording.

In the North American and Japanese interlaced NTSC system, Hi8, which shares the roughly 400 lines of resolution with rival format S-VHS, appeared on the market in 1989, and was formally laid to rest in 2007 – a roughly 18 year lifespan, which is extraordinary when compared to subsequent Sony-supported formats like minidv / DVC (lasting 1995-2009*); bridge format Digital8 (lasting 1999-2007), which offered 480 lines and used the same codec as minidv; and HDV (lasting 2003-2011*), which peaked at 720p and 1080i. (* denotes rough estimates.)

Whereas the VX3’s minidv successors, the VX1000 , VX2000, and VX2100 continue to hold high value among collectors and fetch decent to overheated prices on Ebay, the VX3 ranges from under $100 USD parts machines to fully recapped & serviced units for $500+ USD.

As with any used vintage gear what might look pristine could be a largely non-functional camcorder; and what might look like a well-loved beater could be a tank that survived tough shoots, took a lot of kicks, and still keeps ticking.

Now, the VX3 was and still is a great camera, especially in terms of its ravishing colour reproduction. Unlike the hard black case camcorders that immediately preceded it, the VX3 is less severely affected by bad capacitors and dead pixels, and unlike the problem-plagued V801 and V5000, it’s one of the few models worth getting repaired (if not recapped, if necessary) – but they can be tough to find fully functional. More often they appear as fully restored; “as is” potentially non-functional units with the seller unable to test due to lacking AC adapter or compatible / functional batteries; or they’re pretty messed up, with tape doors stuck open, and missing chunks of their appendages (microphone, shock mount, lens hood & cap) – basically a parts unit.

Minted in May 1994, my first VX3, which I picked up from Ebay about 8 years ago, is physically a beater – the cover for the topside VCR function keys are gone, and the selector wheel for manual adjustments doesn’t make proper contact causing selections for shutter, gain, and F-stops flip all over the place.

Several years ago, I bought my second VX3 off Ebay for a pretty low price, as it was billed as a parts machine, and drilled holes by the onboard mic ledge excepted, it looked really good.

I was very delighted when it turned out to be in almost full working order. Minted in April 1995, the only issues so far are:

The composite input / output RCA socket being a little loose, likely because it was fed into a colour monitor during filming or used for transfers, and all that handling and stress from the cable may have created a cold solder fracture. The viewfinder, which, after powering on in VCR mode, occasionally gets garbled until the camera warms up – likely a sign of capacitors nearing their life expectancy. The issue does go away after the camera’s been on for a while, and (so far) the garbled signal doesn’t affect recording to tape, nor the composite and S-VHS outputs.

The hard rubber lens hood became fragile and subsequently shattered, making it impossible to attach the white lens cover for white white balancing. I’ll have to find a hood that matches the lens’ thread, and a hood diameter onto which the white balance cap fits.

Additionally, like the V801, the rubber section on the hand strap has fractured, and missing is the slot where the lens cap can slide into place and be out of the way.

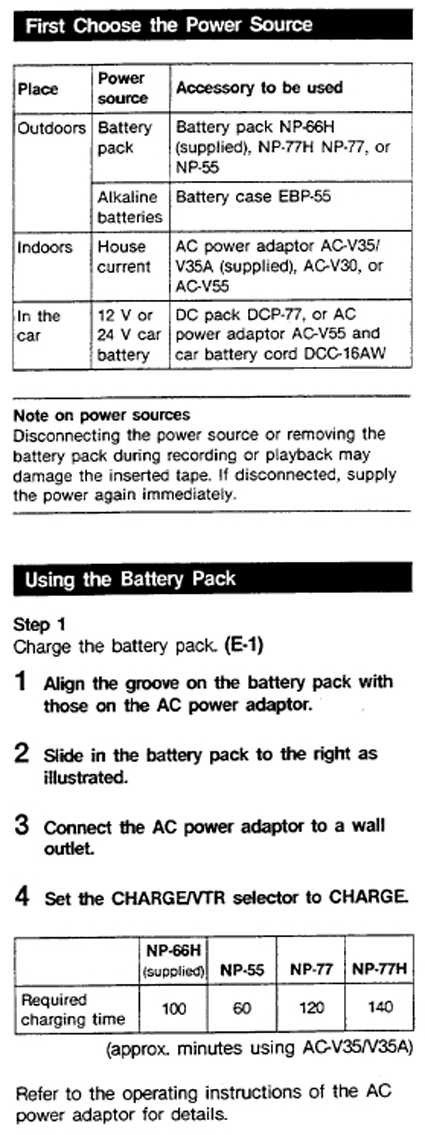

The three camcorders also used the same battery NP types as lower consumer models – types 55, 66, 66H, 77, and 77H – which was a nice gesture Sony later mucked up when new lines mandated (or were force-mandated) new batteries that were incompatible with other models, especially with early Digital8 and minidv models.

It is extremely rare for batteries from the early 1990s to retain any charge, be they Sony-branded, or compatible models by Optex, Powermate, or Varta, to name a few. The same goes for other brands, such as late 1980s and 1990s JVC and Panasonic camcorders with their own proprietary types that have similarly dried out, and have devolved into sturdy, durable doorstops or paperweights.

In terms of powering the VX3, you have 3 choices: the same NP battery type; a NP adapter that requires 6 AA type batteries; and the AC adapter which requires an AC source or a portable battery unit with an AC socket (like a Jackery). In Part 2, I’ll detail these options.

For the camera tests, I used a very simple camera kit, drafted a hit list where footage had to include daylight, dusk, and nighttime filming, and more often than not, the use of the Canon’s C-8 Wide Attachment 67, a crisp wide converter lens designed for use with Canon’s Super 8 cameras (like the 814 which I used in high school), and upper tier consumer tube cameras, such as the VC-50 Pro which I used on two short films to be showcased soon on BHA+.

Although I could’ve recorded the video on a separate Digital8 camcorder that offers a higher quality image, I wanted to show the virtues and limits of Hi8. In Part 2: 3CCDs, Baby! I’ll detail the choice of locations, and have lengthy montages showcasing the VX3’s footage.

Please subscribe to BHA+ on YouTube, and follow me on Facebook and Instagram for gear stills, and an upcoming teaser trailer featuring samples from the extensive VX3 test footage.

Vintage magazines in this piece were provided by BHA+’s main sponsor, Hamza Mughal. Whether you’re interested in selling, donating, or buying vintage broadcast video gear, Hamza is a reliable, trusted colleague and friend who specializes in sleuthing, re-homing, and fulfilling the needs of collectors, filmmakers, video artists, and archivists.

A sizable chunk of gear to be reviewed and showcased at BHA+ was generously donated to The Hasonian (my personal archive) by Hamza, some of which were rescued from the evil recycling shredder, or were idling in a shed or locker or basement, waiting for a new home.

Thanks for reading,

Mark R. Hasan

Publisher, BHA+ / Big Head Amusements