(Mis)Adventures in Video, Part I: the Toaster comes to York University

What was planned as a one-off blog on the Video Toaster and the classic demo videotape available to the curious and interested buyers in 1992 morphed these past weeks into something different during the writing stage, with Part I (yes, it got too big) providing a teasing intro to my brief use of the genuinely revolutionary online editing system available to anyone for far less that a larger broadcast gear setup.

I won’t get into the history of the Commodore Amiga and VT here, but in Part 2 I’ll have some basic info as it relates to Zach Weddington’s 2017 documentary Viva Amiga, plus a review of the film and the myriad extras available via Vimeo. Also in the blog will be short anecdotes of the two projects which helped me and a buddy become masters of our own industrial video domains not long after graduating from York University’s Film Production Program.

Bill and I didn’t make art during that brief co-production period, but the Amiga and VT offered both unique opportunities and the kind of headaches typical of new gear, new software, and long-distance tech support during pre-internet days.

Now before I get into an overview of the way video was eased into each of the four years that comprised York’s program, you might be wondering ‘Hey Mark! What happened to the stock footage that was supposed to be available for royalty-free usage?’

In a nutshell, selling clips on VHX was a test to see how well the interface worked, and the quality of the clips themselves. The interface was fine, but the clips were compressed as MP4s and wouldn’t have suited an editing project unless H264 was the preferred choice. Moreover, when VHX was absorbed by Vimeo in 2017, the communication I had with an account rep over a particular issue stopped, and when the site was re-branded by its new parent, the new incarnation didn’t suit my needs.

Vimeo’s digital downloads portal looks good, but I’m concerned about both compression and the cost of upgrading from Plus to Pro; what I may test out later is a physical release, like a USB stick for uncompressed / less compressed avi and ProRes files, and DVD-R for smaller-sized versions.

Shopify seems like the a more suitable portal to sell physical releases, as I’ve noticed a few video labels also sell their wares through them, and the interface looks pretty smooth and user-friendly. I’ll post further info as things gel together.

* * *

Now then.

When York University invested in a new (and probably its first ever) online editing workstation called the Video Toaster, there was no fanfare within the department and no word to students about this magical toy, probably because the new gear needed to be tested for its strengths & weaknesses, and professors had to figure out how the VT could be integrated into a film production program that was – quite frankly – designed to winnow a mass of roughly 65 ‘Maybe I’ll Become a Filmmaker’ students to those firmly obsessed with moviemaking mechanics, and its specialized career options.

The class sizes were significantly cut each year, and we also lost students who realized that what seemed like a basket weaving class about movies was to them far less interesting than more pragmatic, vanilla disciplines like economics and marketing. I remember one affable guy who always carried a brown briefcase; more than likely, after switching majors, he must have landed a snug job than myself and the remaining 20-odd characters that stuck it out to Year Four.

In Canadian dollars, the basic setup of a VT probably cost around $8000, but to really make use of its goodies and leading function as a live video switcher / special effects generator (SEG), character generator, and editing controller, you needed time base correctors (TBCs) to ensure the video signal was stable and synced to the VCRs; you needed the VCRs (a player + recorder, each – I think – requiring its own TBC), and a lot of patience.

Film Production at York, circa 1987, was on a slow transition phase as it moved from celluloid film to including video starting in Year 2. (The university also had a radio & television course students could take after having completed Film Production Year One, but that alternate stream was scrapped in 1988. The separate screenwriting course remained unscathed.)

I say “slow transition” to video not because Film Production 101 was a poor program, but due to the more gradual evolution of video technology, which still had class and graduate film projects cut on Steenbecks, and videos cut on non-linear offline editing systems. Here’s a breakdown of how my quartet of years – and probably those who preceded my class – went through York’s classic university curriculum that weaved and winnowed students from general basket weavers to genuine film students.

Year One: Film Production with Kathryn Ruth Hope and Teaching Assistant Carl Bessai; Film Theory with Doug Davidson; and electives, of which I chose Man and the Environment with Chester Sadowski + another prof in Term 2, Introduction to Psychology, and 20th Century / Modern American Literature with Mark Kikot. Summer Class: Production Planning with Prof. Hope.

Year Two: Film Production with Vince Vaitiekunas; Film Theory with Scott Ferguson; Screenwriting with Michael Jacot; electives were probably three night school classes, one taken each year: Greek & Roman History, European History, and German History.

Year Three: Film Production with Antonin Lhotsky; half-term Film Editing with Les Brown; half-term Cinematography with Dave Roebuck; and Screenwriting with Václav Táborsky.

Year Four: Film Production with Kathryn Ruth Hope; Video Editing & Production with Dave Roebuck; Screenwriting with David Brady.

I’ll break down the precise projects and learning components of these years in a later blog, but suffice it to say we moved from still cameras and non-sync Super 8 in Year One to sync-Super 8, post-sync 16mm B&W, and SuperBeta I video in Year Two; Year Three had sync 16mm colour film, and 3/4″ U-Matic and Hi8 video; and Year Four was exclusively 16mm film.

I should also add that like the shifting emphasis over four years from stills to sync 16mm colour film, the department itself was transitioning from the bunker environment at the base of the Ross Building to what was called Fine Arts Phase II (later re-branded as the Centre for Film and Theatre).

If my memory hasn’t gotten too fogged up, the shift from the Ross behemoth to FAP II happened just before the start of Year Three, circa the fall of 1989, but it occurred in two stages: while the SuperBeta edit suites were still in the Ross basement, the U-Matic machines were in FAP II; we continued to use the editing benches for film projects in the bowels of Ross, but by Year Four they were fully relocated to FAP II in separate rooms with fire doors and cinder block walls.

We also had access to maybe 3 Steenbecks + 1 Intercine in dedicated rooms. (The north edit suites were for us, and I believe the south edit suites were for students in the graduate film program and us when not in use. I remember using the Intercine several times which seemed designed to play 16mm and Super16.)

Leaping a little further back in time, in 1987 there existed only FAP I (later re-branded Joan & Martin Goldfarb Centre for Fine Arts), which was fronted by a large asphalt bay (now occupied by Accolade West) for the multiple buses that took students to Downsview Station (now called Sheppard West) via Keele. Buses heading to Lansdowne station also pulled into the bus bay, but traveled south using the most horrible combination of residential streets and major roads, with an unreal degree of stop signs. I’m pretty sure the Lansdowne route was jerry-rigged to absorb some of the heavy student traffic otherwise fed into Downsview.

Most of what lay to the east and south of the FAP I and II were expansive parking lots and swathes of grassy hills that could be used for golfing. (A classmate did just that, showing up in screenwriting class in a tweed golfing outfit – hat and knickers – and showing off the whacker that would send those hard white balls into the air. The land was so spread out that he probably managed a modest game without clocking a passerby or squirrel.)

The video gear used in Year Two was basic: the camera was a SuperBetamax unit (no idea of the model), and footage was cut on a pair of Sony GCS-50 VCRs, with the control track enabling the editing console to perform straight linear cuts by pressing a very red button. I made two videos with best buddy Cindy: a short ‘exploration of a place’ filmed in Kensington Market and cut to a guitar track by her future husband, and a documentary on her aunt.

We were also tasked with cutting another short written by / starring Martyn, directed by (methinks) Taras, and shot by Drew who would say “Valium” instead of “Speed” to signify camera was rolling & ready for a take. The few bits Cindy & I cut were erased, so out of revenge I borrowed the master tapes and cut a spoof: instead of chronicling the drunken self-destructive behaviour of a Bukowsky type, I fashioned a faux documentary on the sound recordist (me) who stole the tapes and released his own rogue version called Das Burp, which was released exclusively in the territories of Nordfal and Quebec. Instead of smacking me, Martyn laughed and said “It’s better the fucking original.”

I also cut a faux doc (I think it was called The Curious Tremolo of One Cindee) on the elliptical nature of Cindy’s laugh using outtakes and shots of local streets and York’s former road network leading up to the Ross behemoth circa 1988. I still have to dig for that footage; I’ve no idea of its quality, but it’s all pre-mega construction and shows the original Brutalist architecture which York’s campus 1990s expansion admittedly tries to downplay. There’s bad Brutalism, good Brutalism, and intersting Brutalism which best describes York’s ‘pre-renaissance’ Downsview campus, now shrouded by sexier contemporary, fanciful structures.

This archival still from York’s Alternative Campus Tour site shows the front of the Ross, and the massive concrete ramp which was slowly demolished in 1989 to make way for Vari Hall:

Seen in its shiny grey newness, the central office building is a hulking monster, but to paraphrase Bugs Bunny’s address to Rudolph, the tennis-shoed monster, ‘It’s an interesting hulking monster with interesting poured concrete.’ (Bobby pins, please.)

The York blog infers the ramp and open space were wasteful for the increasingly large student population and expanding courses, and in a more overtly anti-Ross blog, Robert Fisher, an early prof at the new Downsview campus writes “The two wings of [Vari Hall] are connected by corridors with floor-to-ceiling glass. The overall effect is of giant arms welcoming students. Another advantage of Vari Hall is that it hides a good deal of the Ross Building.”

That’s where I disagree, because Vari’s construction was in 1989 puzzling to watch. It looked too close to the Ross, and first impressions of the emerging hall were that it was designed to purposely hide the behemoth and maybe set up its demolition at some future date. Vari’s close proximity isn’t advantageous; it clutters the frontage, but as more buildings were erected and roadways carved into former lots and curving mounts of grass, you can argue the campus’ eclecticism makes York look busier, especially when students migrate from one area to another (or flee from possibly cannibalistic Canada geese).

This second still from the Alternative Tour site shows the Ross from its rear, with an amphitheater separating it from the massive inverted ziggurat library. By 1987, the amphitheater had been replaced by a religious centre which always looked like a two-thirds buried building.

(It’s also perhaps fitting that the centre and the library gave a local cult perfect angles to entrap students, asking them “Would you be interested in a Bible study class?”

This is no bullshit.

At a year-end screening featuring selected works by the class one or two years ahead of us, we saw a video documentary on a girl who lost contact with her friends and family when the so-called ‘Bible study’ baited young adults living far away from home with fake promises of security and spirituality. During the evening’s Intermission, Cindy was approached by one of these twits in the washroom, and not long afterwards I encountered two smiling zombies flanking the walkway leading to the library’s entrance. I just laughed and muttered “Nope” and walked on.)

The highlighted area represents the ‘formal’ entrance into the film department. The doorway led into the small mall, but a sharp left turn and entrance through a fire door led into a narrow metal staircase, and the basement, where we were incarcerated. During the lead-up to the first Gulf War, we were confident that a direct hit to the petroleum reserves a few blocks south-east wouldn’t harm us because Ross’ Brutalist structure would protect us. I mean, look at the fucking thing. It could probably survive a contemporary ‘Bunker Buster.’

This is my last digression (promise), but perhaps the most amusing source of 1987-1988 York from a student’s vantage may lie in the sync-Super 8 film made by Norman. Hell Blazer is about a blazer so ugly it makes unfortunate witnesses vomit day-glo spritzes before keeling over dead.The following frame grabs are from an offline edit Mike & I made in Year Three about Norman, with the Hell Blazer shots taken from a monitor. (The burnt-in time code was used to make note of in & out edit points used for the final online edit.)

Excerpted are the Main Title, the Hell Blazer, and an unfortunate witness (possibly Andre, who would later co-write the 1997 indie CanCon hit Cube with directed Vincenzo Natali).

Alex created the beautifully ugly thing – the thermostat and AC plug (still #2) is novel – and you see an eastward view of the nursing building. To the side rested canted orange girders we all agreed would one day beckon a student stranded on the barren campus to hang itself.

‘Dead Man’s Hanging Tree’ was nestled between the library and the nursing building (not pictured). If you kept walking hard right, you’d hit the mall entrance adjacent to Ross, and the Film Production Department in the basement. Professors had offices in the Ross tower, which also housed the Grad Lounge watering hole where students, TA’s, and definitely one of my favourite profs got a little pickled.

As morbid as it sounds, you were stranded on campus when the weather turned bad. A snowstorm prevented any vehicles from moving, there was no mall, no food vendor open after 6pm, no booze, and after 1am the heating was turned off in FAP II. In Year Four I kept warm by boiling water in a locked Steenback room when not using the whirring editing machine to generate heat.

As I stated, Year Three‘s film project were still done in Ross, while the video projects were done at FAP II.The first project was a documentary; instead of training our Hi8 camera on a subversive cult, Mike & I picked Norman, who’d left after Year One and become an important contributor to Starweek Magazine, writing great pieces on movies and video releases. Before 20, he was already an accredited journalist, and the doc bridged his time at York with current activities and views on cinema.

The other video project was really just an editing assignment.designed to teach us the use of the Sony U-Matic machines and the magic of the EDL, aka the (motherfucking) Edit Decision List.. The 16mm film segment of Year Three was more involving (we had separate cinematography and editing classes), and since winter was so goddamn cold at York, the videos were humane ways to keep us working, learning, but not freezing to death, or eating badly catered Baba ghanoushz.

In our new red FAP II classroom, I remember Roebuck showing us an old portable U-matic recorder and camera (it might have been a Sony DXC-1850, which I still want to own), film prof Lhotsky showing us an actual Quad videotape reel of an old work of his, and we tried out a new high-end Hi8 pro-line camcorder the university bought for about $5,000 or something, but besides learning about the zebra feature in a hallway, I don’t recall any assignments that made us use the huge thing.

The smaller Hi8 camera (model unknown) was used for our Norm documentary, and in addition to filming the interviews and Hell Blazer clips, it also appears in my thesis film, The Bare Bones.

The curse leftover from the analogue era is that while your movie may exist on film, you created a master video transfer and sub-masters for dubbing VHS copies, from which the two frame grabs below originate. That wall behind actor Marc Daniel is supposed to be BLUE. If the money’s ever there, I’d love to do a clean HD transfer from the 16mm A/B rolls, and use the sound from the 35m mono mag mix.

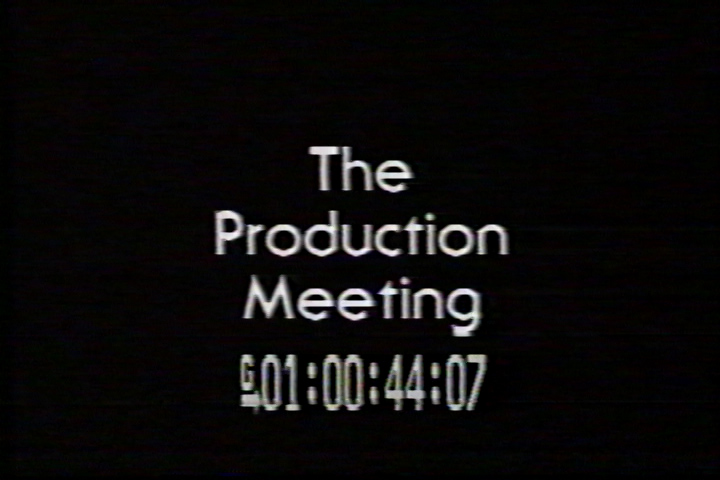

Dave Roebuck’s class was mostly about video production (and the handling of knurled rings). The main footage of our editing assignment was dumped with burnt-in time code to U-Matic, and we had to cut a lengthy dialogue scene tied to a script called The Production Meeting, which actually featured Dwyer Brown (co-star of William Friedkin’s killer Druidic tree thriller The Guardian) in a small role at the very end.

The skill set we were learning included the virtues & quirks of time code, creating a cutting copy using offline machines, and assembling a (motherfucking) EDL. The process was ‘simple’: write down the in / out points of your cuts on a tally sheet using the burnt-in time code, transfer the list to a computer (a Commodore, I think), and then take the (motherfucking) EDL to the online suite where the software would fast-forward & rewind the master tapes, play the needed sections and initiate the cuts.

The (motherfucking) EDL had to work, which it often didn’t – sometimes the revised in / out edit points weren’t or didn’t ‘ripple’ down and update the rest of the coordinates – so the workaround was to do manually cuts. The (motherfucking) EDL is evil, and it kind of drove me and Mike a little crazy trying to make sense of the footage, the variety of takes, and our increasingly toasty mental states in that windowless cinder block closet.

Here’s some snapshots of the cast & characters we saw Every. Single. Class.

I tried humour to ‘lighten’ our fluorescent closet, but Mike almost killed me after I kept teasing him about second-guessing an agreed-upon cut.

Like a finely timed Daffy Duck cartoon, I’d lunge forward just as he was about to press down EDIT, and shout “Wait!!! MIKE! Are you SURE you want to press that RED BUTTON? Because once you do, the edit CANNOT be undone! There is NO BLUE BUTTON… THINK ABOUT IT!!!”

At one point his visage went from upset to a murderous grin that widened under two glassy, bloodthirsty eyes, and it was then and there that I realized through slow and steady and carefully chosen and paced words I could drive people crazy. (I still possess this skill). Things worked out swell in the end, because along with Norman and Martyn, I was part of his groomsmen party for what remains the best wedding I ever attended, but Mike’s exasperated, semi-Soup Nazi ‘You’re pushing your luck, Little Man’ look was and remains priceless.

Our edit of The Production Meeting was pretty good, but tangential to the endeavor, I also ended up with the best thing I’ve ever edited, although after the fact. I created not a mash-up of our editing project, but something very special.

I wrote out a new narrative using select dialogue from the master footage, used select takes and cutaways, and what became a banal meeting between a producer, and agent, a director, and the coffee maker CEO wanting a great advert was elaborated into a series of arguments and realizations using footage from Caligua and Suspiria. (It kills me that I can’t post it because, well, there is some ‘medium’ adult content.)

Now then.

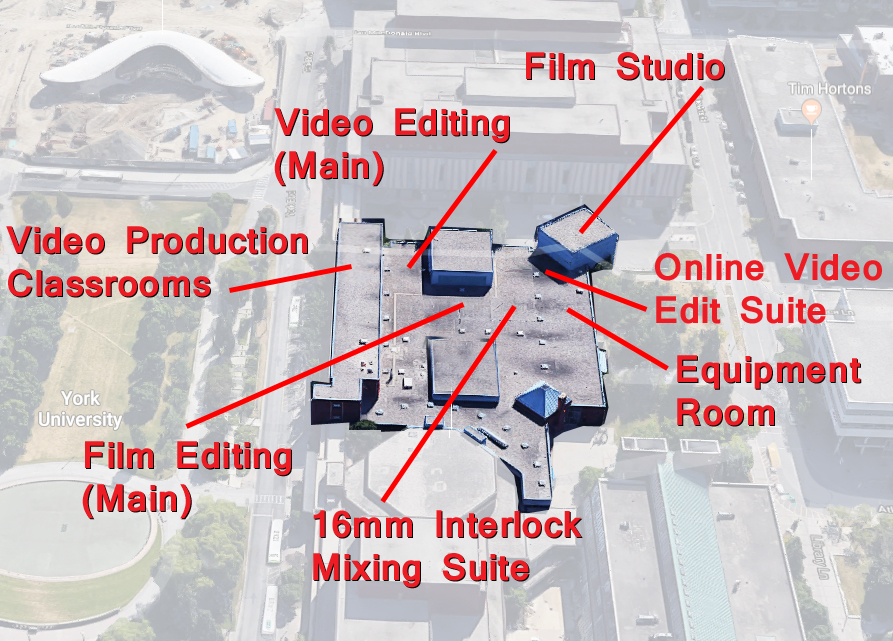

I think it was around the end of Year 3 when Roebuck’s management of the new online edit studio and adjacent sound stage was finally coming together, and the room was very pretty, with U-matic SP VCRs, a Hi8 VCR, rack-mounted vertical interval switchers, a Sony SEG / edit controller, and a wall of monitors for the editing and live camera feeds from the studio.I’m pretty sure this is where we fed our (motherfucking) EDL’s into the system to complete our Norman doc and The Production Meeting (whereas my abomination was done in secret, using offline gear in a locked room).

What hadn’t yet been installed was the Video Toaster, but it was in the building.

In Year Four, some classmates used the studio adjacent to the online suite for their final theses, and there was also the class picture taken in the studio, in which everyone was all shiny faced, and every male had a magical full head of beautiful hair. (As Kiarash once remarked, if there had been a Best Beard of York U, I would’ve won a few times.)

I’m pretty sure my first glimpse of the VT set-up happened in Year Four when I needed to chat with Tim Richards about doing the company logo for my graduate film.

Fun Factoid: the reason all post-1991 York U films must have the closing line ‘Produced at York University’ or something close to that is due to US. We created company names because it was fun,and in my case, I wanted to sell the films as the first productions from my company. (Around Year Two we were shown a terribly melodrama short starring Jerome Godboo no one liked, and yet we shut up after the prof said ‘And they sold it to Japanese TV for $8000.”)

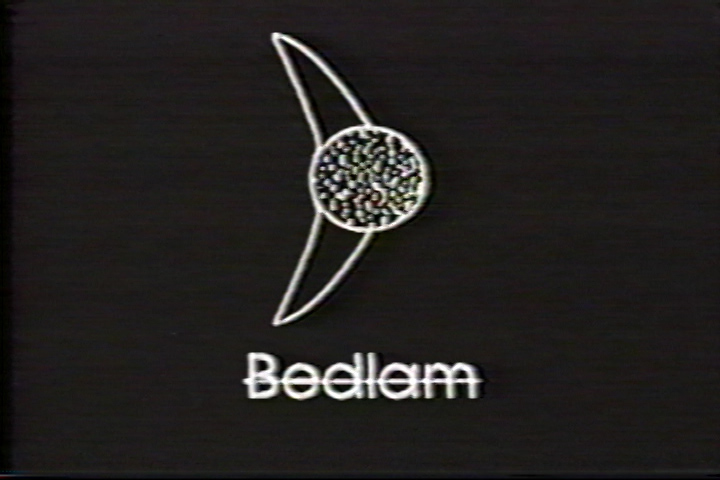

Andrew created RAMA Films (still #1), and mine was Bedlam Productions (still #2) with an animated logo that cost $1500 circa 1990 to render on film. It was worth every penny. Look how pretty they be:

The other reason for dropping York from the credits was a passive-aggressive retaliation to the bickering within the Film Department’s professors, half of whom refused to allow us a graduating screening at the Bloor, but Prof. Hope told us “You’ll have your screening. I promise,” and she delivered. You can criticized teachers for human failings and organizational flaws, but she fought for us, and she has my eternal respect for standing up to tightwads who sought to deny us a screening after some of us dropped a fortune to earn our degree; in 1991 dollars, I blew over $21,000. Not peanuts by any standard.

So yes, blame us for that mandatory credit.

Getting back the narrative of this blog, the room that housed the VT was warm from the computer and VCR gear, and on a screen was the VT’s unique logo. I’m pretty sure I asked Tim Richards ‘What is that?’ and kind of went ‘Oh’ because it just looked a little underwhelming. Dim illumination, the sound of fan blowers, and this image on the monitor:

There weren’t any sample videos or sexxxy things Tim could show us because it seemed as though the VT had just been set up and he was trying to learn the basics of what is still regarded as an important stepping stone towards the creation of a standalone workstation. You still needed VCRs and a lot of peripheral gear, but the VT’s creators at Newtek certainly took the concept of turning anyone into a self-sufficient filmmaker from fanciful idea to reality.

My conversation with Tim involved not the VT but taking my logo sketches and outputting them to acetate sheets, which I later gave to The Animation Group (they did a lovely job), and the next time I saw the VT was after I graduated in 1991, and York had integrated the workstation into their snazzy online edit suite.

Just to reiterate: my class never had the privilege of doing anything substantive in the online suite, but we did make use of the adjacent studio – Earl used its entirety for his short The Last Draw (1991) about a gambler who plays a game with the devil, and Xenia used it for her short about a world that existed inside someone’s mouth.

All of our films were weird. Mine, The Bare Bones, dealt with a man who hacks up his neighbour, tosses the remains throughout the Scarborough Bluffs, and finds himself the target of the dead man’s vengeful son. It won a cinematography award because of Darrell Maclean’s fine lensing and incredible ingenuity. Dude built a crane for the production, which we dubbed the McCrane.

Like many film production graduates, after completing a 4 year course and spending a then outrageous $1300 a year for tuition (not to mention $15,000 on my own film, since we had to produce a full answer print), the logical move was to apply our production skills and earn a living, and around 1992, me and Bill made a corporate video for an accounting firm. Since York had an edit suite, it seemed logical to rent it for the production, and that was our first actual use of a non-linear editing set up with some assistance courtesy of the Video Toaster – details of which will follow very shortly.

I know. This entire blog was a cruel teaser for Part 2, which will feature the Revolution video and early sentiments on the VT.

Thanks for reading,

Mark R. Hasan, Editor

Big Head Amusement