(Mis)Adventures in Video, Part II: Revolution + Viva Amiga!

Note: direct links to NewTek‘s Video Toaster Revolution demo video and my extensive review of Zach Weddington’s zippy documentary Viva Amiga (2017) are at the end of this lengthy preamble.

After graduating from York University’s Film Production program, the inevitable question was Now What?

There wasn’t any fear or worry, just a sense of quiet curiosity and slight nervousness in wondering what act would follow, or rather begin the phase of a post-graduate life, as each classmate was hungry to apply their freshly certified filmmaker skills.

As I detailed in Part 1, my class was a bit unique in which almost everyone made their own film. We still had to fulfill a series of major & minor roles on other people’s productions, so adding your own thesis film to the roster ensured everyone had more than two roles to appease the overlords for Year Four.

The year-end screening was a highlight, but because there were so many films, it ended up being a more than 3+ hour afternoon / evening, and we lost about half the audience during the Intermission because people were exhausted. Sound troubles also mucked up some playback. In the second half, Jacqueline’s film (for which I did sound editing) was too quiet, as was mine, and it was early into Tim’s film that the sound was boosted when Tim hurried up to the booth and demanded whomever was up there turn up the damn volume.

Tim’s and all subsequent films were played too loud, but hey, we’d had our premiere, just as Prof. Kathryn Ruth Hope had promised. After the screening, we enjoyed beer on the terrace of a pub, and I think we ambled down to Ontario place and bummeled about until it was time to call it a night. When I came home, the answering machine blinking, and waiting was a flattering message from Alex, congratulating me on a job well done. I never erased that message – it meant too much.

The first real Now What? moment happened when Jacquie and I had a burger at a pub on Yonge, close to Steeles, I believe, which has since been transformed into blocks of condos and townhomes. When Bill would accept a job as chief multimedia guru for a finance company, he not only worked close by at Sheppard & Yonge, but lived in one of the new condos. That whole stretch of Yonge from Steeles to Sheppard was already being transformed from sleepy two-story indie businesses to the downtown planned by North York’s mayor Mel Lastman, soon to become the first mayor of megacity Toronto after piece of shit Premiere Mike Harris forced an amalgamation of boroughs and cities into a larger Toronto, downloading assorted services from the province to the city. It’s one of the reasons Toronto’s transit system remains the only major system lacking regular funding from upper tier governments.

During Year Four, myself and a few classmates already had ideas on what might come next. Earl was already flying to Vegas and buying rare animation cels for a niche business he ultimately built up and ran with partner Marci in Toronto and later La Jolla, California; Shay and friend Evan moved into corporate and wedding videos; and Raj was co-managing his dad’s video shop in Brampton, after which he’d open his own store called Penguin Video.

It was actually Raj’s dad that gave me the idea of starting a video conversion & duplication business, in which tapes from Europe were converted from PAL and SECAM to North American NTSC and visa versa, and tapes of weddings and corporate videos were duplicated in consumer formats like VHS. I’d drive out to Canotech’s office in Mississauga to buy custom length tapes (usually 35 mins, 65 mins, and 130 mins) and standard black 1/3 sleeve Amaray-style cases for client orders.

That summer after graduating I’d also started submitting films to various film festivals as a means to set up Bedlam Productions as a new filmmaking venture. Things seemed perfect, as I’d spent money finishing three 16mm shorts – The Bare Bones, Paradise Unfolded, and Neon Niagara – to actual prints, done 1″ video broadcast transfers, and branded each with the BP company logo.

I’d started to invest in the video gear to convert and dub videos – VHS, U-Matic, S-VHS, and Hi8 – and by 1992 those ventures and the minor success (more like the stability) of BP was underway. The summer of 1992 is when Bill & I made an accounting demo video, and used the VT for the first time, and things felt good.

For me, a bumbling orphan at 21, it was the happiest period after some personal hits, but little did I know a car accident later that fall would turn everything upside down, and I’d realign attention from filmmaking to scriptwriting; I’d stick with the video dubs until roughly 1999, folding the dubbing operations as my clients – video stores – were increasingly calling it quits. Most of my business came from Video 99 franchises and two Videophile locations, and when the last Videophile at Finch & Victoria Park closed, that’s when I decided to put filmmaking on pause and shift to writing about movies and filmmusic for a very long time.

In 1991, the technical differences between film and video were stark: film was shot at 24 fps on 16mm and 35mm film, and video at 30 fps on prosumer formats like Hi8 and S-VHS, or Betacam SP if you had better dough. You never shot on VHS or Video 8 because it was the lowest resolution format, and making any copies from a 250 line master didn’t look pretty. (Super 8 was more for the experimental realm than commercial, except perhaps in stylized TV ads; I remember one lab kept a pair in working order for commercial clients.)

Film was for serious filmmakers, and video for industrial, corporate, wedding, and personal projects; a few gambled on SOV (shot on video) horror films to make a name for themselves (Spine from 1986 comes to mind, made by a pair of sexploitation filmmakers using Ikegami ENG cameras and U-Matic decks), but the standard of quality was film; video was simply regarded as cheap, and made any dramatic venture look amateurish. The sharp divide and stern attitude from peers meant if you wanted to make a demo video to show off your skills and enter feature filmmaking, it had to be on film. My thesis costs $15K using student rates; a formal indie short would run close to $20K – twice of what I’d spent to set up the video dubbing business.

It’s one of the reasons I stuck with video post-production, and after the three films had done the festival rounds, What Now? didn’t include another 16mm production. Besides, the Yellow Pages ad and some word-of-mouth was generating queries for demo videos, and everything seemed to be progressing towards steady business prospects, and key to our first venture was Bill’s VT set up, which he’d bought around 1992. The VT was a new animal because it was software-based, whereas my editing setup was a pair of classic U-Matic VCRs that each weighed 130 pounds.

An analogue non-linear system, in which you made a succession of irreversible straight cuts / dissolves / wipes, seemed archaic compared to connecting two smaller / lighter / better S-VHS VCRs to the Amiga system, and used the VT to create those same cuts and sexier transitions. It was still non-linear, but the quality of S-VHS versus U-Matic – roughly 450 lines vs. 250 (or 300 at best) – was striking.

U-Matic did have an edge over S-VHS and Hi8, though: multiple copies made from U-Matic would look ringy – you’d get some dot-crawling on text as well – but S-VHS absolutely mandated TBCs designed to tackle colour offsets that worsened with each subsequent generation. The master footage on S-VHS looked good, but without a TBC you’d get a kind of halo: a woman with pink lipstick and blue suit would have a slight colour haze to the right, as the blue from the suit and pink from the lipstick appeared to be off by a millimeter, and the drift worsened with each dub.

The TBCs in Bill’s JVC machines were amazing – they killed the haze – and when out edited master of the accounting video was done, it needed extra cleanup and we found the software International Image developed reset the flaws so we could deliver a decent master to the client.

In Part 3 I’ll offer more details on our corporate venture and the hiccups Bill encountered with his new Video Toaster setup, but I’ll close with links to NewTek’s still snappy Revolution video which I’ve digitized, colour corrected, and edited & remixed the 2.0 stereo soundtrack into 5.1.

Note: at present, neither Vimeo nor YouTube offer 5.1 streaming, so rather than rely on their respective algorithms to fold the 5 tracks into 2, I did a 2.0 surround sound mix which restricts the voice of Ken Nordine to the centre channel, sets the two front surrounds to the stereo image with slight centre bleed, and placed the rear surrounds with slight delay in the front stereo channels, with their higher range cutting through the mids and low frequencies. It kind of works, but the 5.1 mix is more fun because Nordine’s narration consists of a product announcer and an alternate echoey fanboy expressing awe as each VT feature is demonstrated.

The script is over-hyped and quite funny (“Look at what it can do!”) but the direction by Tony Stutterheim is very slick, packing in as many wipes to show off the Toaster’s sexy design. The fast motions aren’t ADD; they’re as organic as the self-described organic wipes which constantly transition to further revelations of the VT’s features-within-features.

Stutterheim’s background lay in effects supervision, and Revolution won an ADDY (American Advertising Award) in 1991. In addition to showing off the visuals, there’s the character generator that came built-in with the system – a major component, given a quality CG with smooth scrolling and diverse fonts cost a fortune. In terms of value, even if you used the VT as a pass-through to overlay footage, it was a great buy.

Lightwave 3D was another built-in component, and enabled 3D rendering of assorted graphics which were used in series like Babylon 5 (1994-1998) and seaquest DSV (1993-1996), plus several music videos.

Excerpted in Revolution is footage from a Todd Rungren video, and the underwater effects seen in the follow-up demo Revolution 2.0 were extensively used in seaquest DSV, for which Stutterheim was Visual Effects Supervisor / Lead CGI Artist. (Some of the animated material appeared in the Mind’s Eye DVD series which showcased computer-generated art, and I’ll have reviews of select volumes at a later date at KQEK.com.)

You can’t talk about the VT without mentioning Kiki Stockhammer, the model / actress / VT guru who appears in the video and was reportedly the basis of several wipes that featured twirling legs, and other silhouettes of a lithe figure; they were cheesy then, and are perhaps politically incorrect today, but in fairness some of the Toaster’s most oddball wipes provided exhausted editors with needed laughs. There were more than a few occasions when we’d play back Very Serious subject matter and have the wipe be a leg twirl, or a mass of fast-falling sheep silhouettes (which also appear in the demo video).

Stockhammer became a major component of the VT’s public face, and although she left NewTek a few years later, she returned to the fold and can be seen in several industry Q&As on YouTube. In this one she’s bemused by veteran VT users who lined up and asked to have her autograph copies of this classic demo videotape. (if I’d been there, I’d have done the same.)

Revolution was made to sell the VT’s wares and instill excitement in burgeoning and steady filmmakers wanting something dynamic, designed by software engineers with a sense of cheekiness. I don’t know if these two moments within the demo came from Stutterheim, but NewTek’s logo flattening a butterfly in a quiet field of grass and posies is a direct homage to Marv Newland’s Bambi Meets Godzilla (1969), and early in the doc when there’s a montage and ad pap of ‘With it Guys with smart brains’ the x-ray shot of a head and layers of data streams recall the opening title of The Six Million Dollar Man that emphasizes the building of a new kind of human being that’s “better, stronger, faster” – words that also apply to both the VT and Amiga.

NewTek offered the Revolution demo on D2, 1″, Betacam SP, 3/4″ U-Matic SP, MII, S-VHS, and Hi8 formats, but copies sold on Ebay are all from this VHS particular mailer.

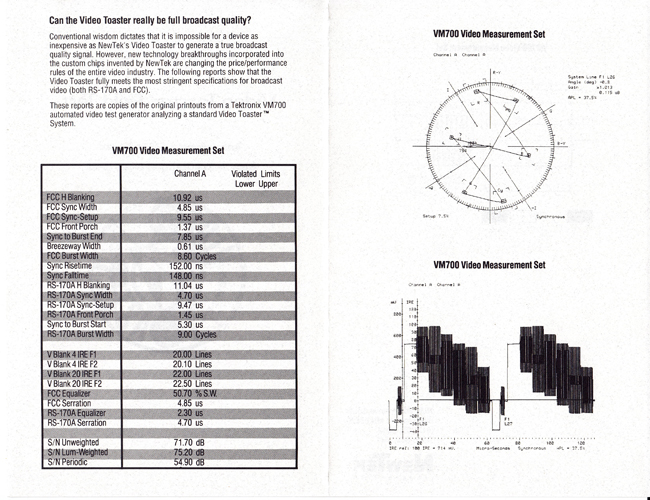

Tucked inside were a series of pamphlets:

The final segment where ‘the Revolution Continues’ is called “System 2.0” and features Yello’s “Hawaiian Chance” from the 1987 album Once Chance which I remember playing over a chase sequence in an episode of Miami Vice.

And the last insert contained some slight tech talk:

If Vimeo and YouTube manage to offer 5.1 playback of submitted files, I’ll revise the links, but for now there’s the de-oomphed 2.0 surround sound version.

Vimeo:

YouTube:

Part 3 will feature some details of my brief flings using the Video Toaster in two productions, and the years I was zipping back & forth between video store franchises and clients, picking up tapes and returning converted dubs until the video store business started to really show signs of a shift in consumer habits, and the effects of Blockbuster’s full assault on classic mom & pop shops took their toll.

Lastly, in poking around for information on the VT and the Amiga system, I discovered someone had made not only a documentary on the computer, but added a wealth of outtakes and extended interviews (many for free), so please jump to the review of Viva Amiga at KQEK.com where I dissect the doc (63 mins), the free extras (172 mins), and a separate raw interview (94 mins) that are available from filmmaker Zach Weddington via Vimeo.

Lastly, in poking around for information on the VT and the Amiga system, I discovered someone had made not only a documentary on the computer, but added a wealth of outtakes and extended interviews (many for free), so please jump to the review of Viva Amiga at KQEK.com where I dissect the doc (63 mins), the free extras (172 mins), and a separate raw interview (94 mins) that are available from filmmaker Zach Weddington via Vimeo.

Yes, I really did watch 5.5 hours of material on the Amiga, and at the end of the review are links to another site offering additional archival materials on the iconic and much loved computer that deserved a longer life. What I would love to see next is a similarly affectionate doc on NewTek and the VT, tracing the software’s design, the engineering of its gear, and its impact on an industry once dominated by large corporations and very pricey chunky gear (some of which I’ve picked up on Ebay for decent to ridiculously low prices).

Thanks for reading,

Mark R. Hasan, Editor

Big Head Amusement